Art of the Far North

Arctic artwork referred to as Cape Dorset comes from Baffin Island in Canada, which lies just west of Greenland. An endeavor to establish some sort of fledgling artist community began at an Inuit hamlet on the southern shoreline of the island beginning in the early 1950’s, which quickly blossomed, and its success went on to become legendary. What Florence meant to European art during the Renaissance, Cape Dorset can equally claim title to regarding art from the Far North over the past 60 years.

Canadian James Houston worked and traveled during the late 1940’s in what was then the Northwest Territories and is now the territory of Nunavut. An artist himself, James was wholly surprised by the Inuit carvings he encountered. Realizing their potential, he became instrumental in beginning to develop an infrastructure in order to support sculpting by the Inuit people as a profitable endeavor.

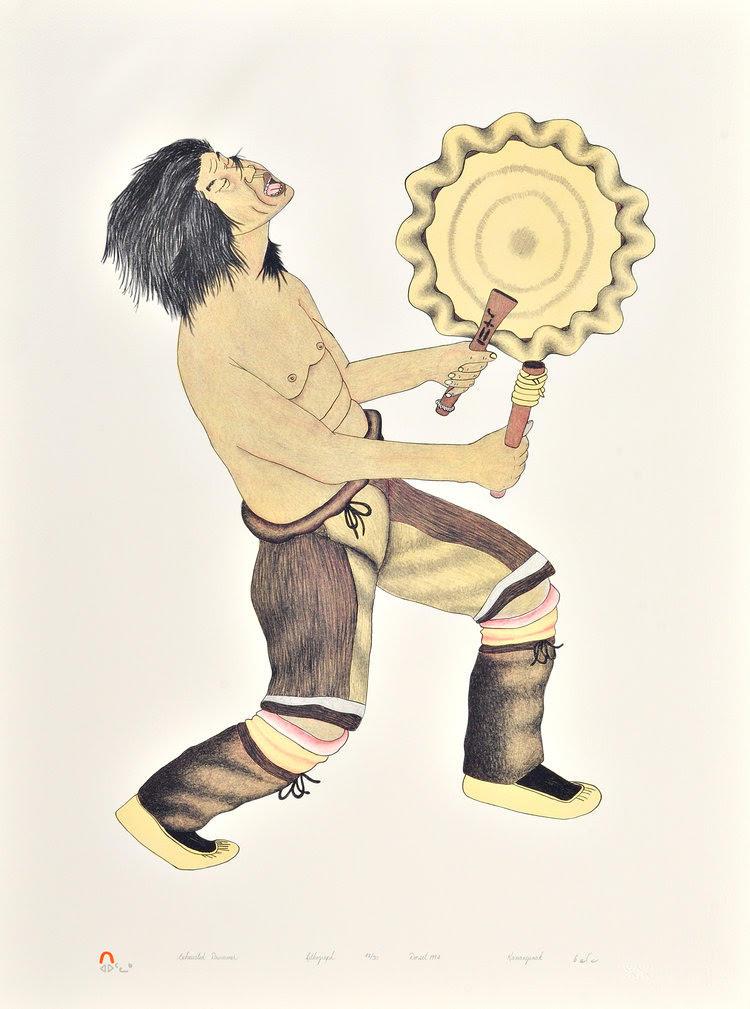

Houston also began working with local artists who made rudimentary drawings, eventually developing a print studio at the growing community of Kinngait, more commonly known as Cape Dorset. An alchemy of Japanese printmaking techniques, which Houston had learned on a trip there in 1956, and Inuit concepts regarding local stone for engraving images coalesced into innovative print types. The prints produced at Cape Dorset, such as the stonecut method that’s still in use today, were the first ever done, let alone in such a remote location.

Further development occurred when Canadian Terry Ryan went north after graduating from college and became involved with the community in 1960. Ryan soon increased the marketing and visibility aspect of the artwork being produced. He became the first manager of the recently established West Baffin Island Eskimo Cooperative (WBEC), now known as Kinngait Studios. It was a position he held for 30 years while guiding it through politics, economic challenges, and ever shifting logistical demands.

Numerous locals soon took up sculpting, drawing, and printmaking during the early years of the WBEC and, by the mid 1960’s, Cape Dorset prints and sculptures were showing up and then quickly selling out in galleries around the world. These initial artists of WBEC had all grown up out on the land. Raised in the seasonal hunting camps, they had listened to intimate retellings of their forebearers’ traditional lives, along with the stories of the old spiritual beings and truths.

The WBEC had become the art center for all Northern Canada by the late 1960’s and by the 1990’s, per capita-wise, the ever expanding village had the highest percentage of artists of any community in Canada. Not only were the people of this region drawn to Cape Dorset for the opportunity that it offered, their artistic inclinations were being encouraged, developed, and supported by what had been so thoroughly established.

This would also lead to a new generation of artists with a somewhat different background—individuals primarily raised in the village. Scenes of Inuit life depicted in their prints began to contain elements of the Western world; snowmachines and motorized skiffs replaced dog sled teams and kayaks . Additionally, the amount of art being produced and placed on the market, by both the older and newer generation of artists, required more infrastructure.

Dorset Fine Arts was established in 1978 in Toronto and became the wholesale marketing arm and distribution outlet for the WBEC. Part office complex, part warehouse, part gallery and showroom, Dorset Fine Arts only offers works to member galleries around the world, who then make them available to the public.

Objects that Westerners consider artwork have long been produced in the Far North, long before the WBEC came into existence in 1960. During the past 60 years of tremendous artistic success on Baffin Island, artwork by other Northern Peoples continued to occur throughout the Arctic, Peoples who had no knowledge of Cape Dorset. For example, traditional artists in Alaska were and still are making works that are wholly distinctive to their region and cultural perspectives.

Today, however, a number of younger artists elsewhere in Canada and in Alaska, who incorporate contemporary art perspectives into their works, are now aware of and have been influenced by the WBEC. Dancing Bear sculptures, a proliferation of owls in print and sculpture, transformation pieces in mediums other than masks, depictions of Sedna and Narwhals by current Indigenous artists in those locations pay homage to the legacy established at Cape Dorset.

Kinngait Studios on Baffin Island and Dorset Fine Arts in Toronto continue on as they have been for some time now. Stiff competition occurs, however. At the community of Cape Dorset itself, at least one other art outlet for artists has opened for business. In other nearby communities, other art ventures or cooperatives have been established to include a web presence. Additionally, there’s the unforeseen competition that every art genre eventually faces—the return of older works onto the secondary art market.

The West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative could not foresee that it would become such a huge success when it commenced in 1960. But, it was never intended to be an end in and of itself. Its foundational vision served to establish an opportunity to develop an art community in the region, to support local artists, and then for the artists to have opportunities for their works to be sold on the market.

Most likely, Kinngait Studios will continue for decades into the future. Whether it does or doesn’t last for another 60 years misses the point; it established something both successful and important—as long as there are Indigenous People living in the Far North, the artwork they produce will be known, respected and available throughout the world.

For sixty years now the Co-op has been a self-sustaining enterprise devoted to the development and promotion of fine art from Cape Dorset. For the first time, we have applied for and received some significant grants from both the Canadian and Nunavut governments to conduct workshops and other initiatives to prepare the way for the next generation of artists in Cape Dorset at a time when a good infusion of creative stimulation is what the Co-op requires. We are therefore confident that Kinngait Studios and Dorset Fine Arts will be ‘staying the course’ for many years to come.

—John Western, Dorset Fine Arts, Sculptures Manager